The opioid epidemic has been a growing problem in the United States for decades. And in 2017, its devastating effects were impacting more people than ever before.

“2017 was the peak of our opioid epidemic in terms of drug overdose deaths—there were 70,237 people who died from drug overdoses in the U.S. that year,” said Jennifer Attonito, a contributing faculty member in Walden University’s School of Health Sciences.

Of those overdose deaths, opioids were involved in 47,600—nearly 68%.1

These alarming statistics prompted the White House in 2017 to officially declare the opioid epidemic a public health emergency. The country has responded with programs to prevent and treat opioid use disorder and to educate the public about the risks of opioid use.

To effectively address the opioid crisis and create lasting social change, we must first understand the path that got us here, said Attonito, who holds a PhD in Public Health and has published many studies on drug use problems in the U.S. Attonito also serves on an opioid task force in her home state of Florida and is involved in other programs that aim to address this urgent public health problem.

How did the opioid crisis get to where it is today? Attonito said the current opioid crisis began to take hold in the 1990s and developed in three phases:1

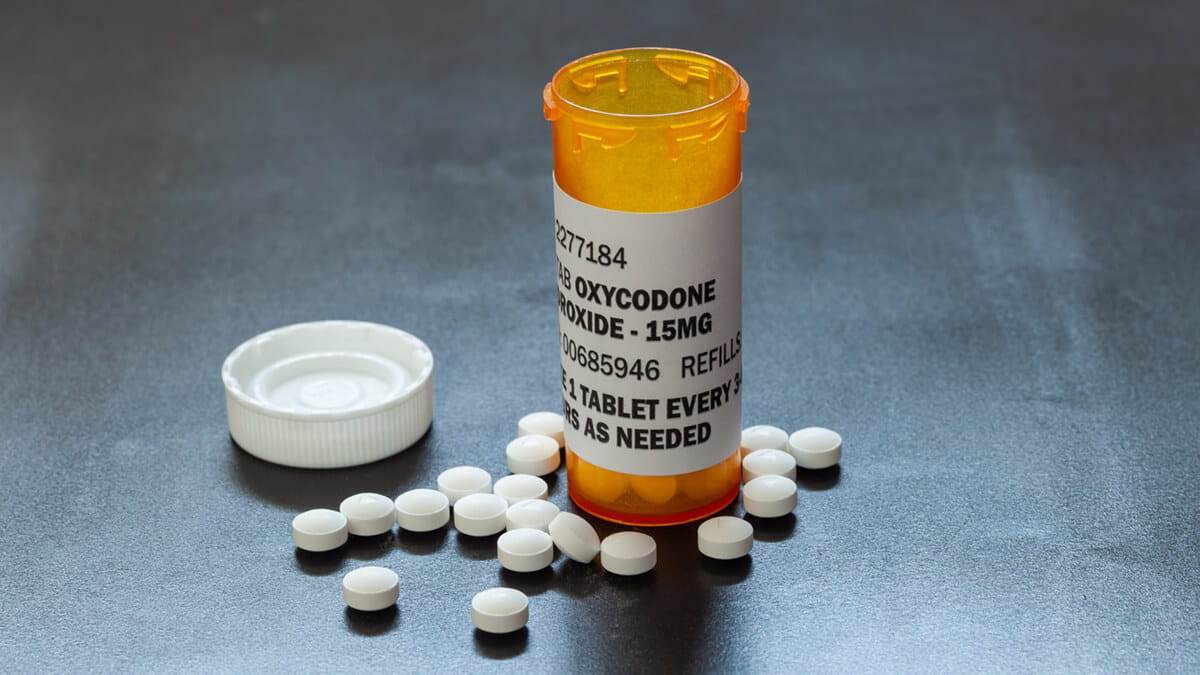

Phase 1: There was an increase in prescribing opioids in the 1990s. Since that time, national death rates from prescription opioid pain reliever overdoses quadrupled from 1999 to 2010.2

Attonito said one likely contributor to this increase in the prescribing rate was a 1986 report (Portnoy and Foley) that suggested that that opioids were a safe, non-addictive alternative to surgery or no treatment in patients with chronic pain.

Phase 2: In 2010, the U.S. saw a rise in overdose deaths involving heroin—the death rate from heroin overdose doubled from 2010 to 2012, according to data from 28 states.2 Heroin is a type of opioid that is often more readily accessible, less expensive, and offers a more potent high than prescription opioids.

How did the increase of prescription opioids affect this increase in heroin deaths? Attonito points to a study of young, urban injection drug users interviewed in 2008 and 2009.“Of those interviewed, 86% of people who were heroin users started out using opioids,” she said.

Phase 3: In 2013, the U.S. saw a significant increase in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids— particularly those involving fentanyl, a powerful man-made opioid that is been illegally manufactured and sold on the streets. In 2017, nearly 60% of opioid-related deaths involved fentanyl, compared to 14% in 2010.3

“The synthetic opioids, other than methadone, have been the culprit of most opioid overdose drug deaths, especially between 2014 and 2017,” Attonito said.

What’s Next?

Many public health professionals consider opioid overdose as the biggest public health threat of our time. Solving the problem is a complex job that will take years of coordinated effort between public health professionals, healthcare workers, government agencies, community leaders, and policy makers.

The good news, said Attonito, is there has been some degree of progress since the opioid public health crisis peaked in 2017. For instance, total drug overdose deaths in the U.S. dropped about 4% from 2017 to 2018.4

“We are starting to see improvement, but it’s going to take time,” Attonito said. “This is just the beginning of our effort to stop the problem.”

As we move forward, Attonito points to the following strategies as critical in solving the public health crisis:

- Expand access to public funding for treatment

- Continue research of treatment modalities and medication-assisted treatment

- Secure ongoing federal funding until overdose rates stabilize

- Establish quality standards for sober homes

- Fund large-scale early prevention interventions

- Promote research-based prevention and treatment programs and public health campaigns

If the past is any indication, said Attonito, a nationwide effort to stop this public health problem can create positive social change—as we saw with the effort to prevent smoking in the U.S.

“At its highest peak, about 50% of the adult population was smoking back in the 1950s, and today that has been reduced so that now the U.S. has one of the lowest smoking rates of the developed world,” she said. “This required multiple efforts—from public education to smoking cessation programs to behavioral interventions—and they were powerful and consistent, and as a result, smoking is highly unpopular today.”

Help Fight the Opioid Crisis with a Public Health Degree

Many public health professionals are equipping themselves with the tools needed to combat the opioid crisis by earning a master’s degree or doctoral degree in public health.

Walden University is a great choice if you want an online public health degree program that can help you expand your impact and career options. The accredited university offers Master of Public Health, Doctor of Public Health, and PhD in Public Health degree programs online.

Creative solutions require new knowledge. Further your college education and grow your public health expertise with an advanced public health degree.

For additional information on this topic, you may wish to watch Walden’s webinar entitled, “Opioid Epidemic: How Did It Happen and Where Is It Headed?”

Walden University is an accredited institution offering Master of Public Health, Doctor of Public Health, PhD in Public Health, and BS in Public Health degree programs online. Walden’s MPH program has received Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) accreditation. Expand your career options and earn your degree in a convenient, flexible format that fits your busy life.

1Source: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose

2Source: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6339a1.htm<

3Source: www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/fentanyl

4Source: www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db356.htm

Program accreditation: The Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) Board of Councilors acted at its September 6, 2019, meeting to accredit the Master of Public Health program at Walden University for a five-year term. Based on CEPH procedures and the documentation submitted, the program’s initial accreditation date will be recorded as February 3, 2018. CEPH is an independent agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education to accredit schools of public health and programs of public health. CEPH accreditation provides assurance that the program has been evaluated and met accepted public health profession standards in practice, research, and service. For a copy of the final self-study document and/or final accreditation report, please contact the dean of the College of Health Sciences and Public Policy ([email protected]).

Note on certification: The National Board of Public Health Examiners (NBPHE) offers the Certified in Public Health (CPH) credential as a voluntary core credential for public health professionals. Individuals who have a bachelor’s degree and at least five subsequent years of public health work experience will be eligible to take the CPH exam. However, for individuals without these qualifications, a candidate must be a graduate of a school or program of public health accredited by the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH). Walden’s MPH program’s initial CEPH accreditation date was recorded as February 3, 2018.

Students should evaluate all requirements related to national credentialing agencies and exams for the state in which he or she intends to practice. Walden makes no representations or guarantee that completion of Walden coursework or programs will permit an individual to obtain national certification. For more information about the CPH credential, students should visit www.nbphe.org.

Walden University is accredited by The Higher Learning Commission, www.hlcommission.org.