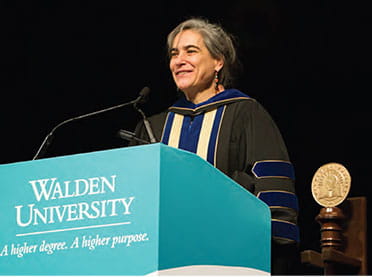

Sarah Chayes, an author, social entrepreneur, and policymaker who lived among the people of Afghanistan during much of the war, shares her hard-earned lessons for effecting change.

Sarah Chayes

Photo credit: Jenny Abreau

Sarah Chayes is focused on determination, not hope. Hope, she says, doesn’t take into account the effort required—it’s an almost-blind presumption that things will somehow go well. Determination means you’re committed to putting in the work. Chayes knows what she’s talking about. She started her career as a journalist, reporting on the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan for National Public Radio and felt compelled to stay to help rebuild the country. After running a nongovernmental organization and founding a manufacturing cooperative, she was tapped in 2009 to advise the command of the international troops in Afghanistan. She went on to work for the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Now a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, she is finishing her second book. Before her January 2014 speech at commencement in Orlando, Florida, she sat down to talk about how our graduates can effect change in their own communities.

HOW DID YOU BECOME A SPECIAL ADVISER TO THE CHAIRMAN OF THE JOINT CHIEFS OF STAFF?

CHAYES The military reached out to me. I was an American who had been living in Kandahar, outside the wire, embedded in the population and speaking the language. They lacked direct, unmediated interaction with ordinary Afghans. There was a communications gap.

I had discovered that what was making Afghans angry at the international intervention was not ‘Western culture’ or religious differences, but corruption. They blamed us for the criminal behavior of the Afghan government—which they saw us supporting.

This is not garden-variety corruption. The system is vertically integrated. In return for kickbacks that subordinates pay to their superiors, they receive protection. That means if you go after a provincial border police official, for example, President [Hamid] Karzai himself will step in to protect him. This critical problem was beyond the scope of a battalion commander to tackle—and even of the top brass. Once a chief of state is involved, issues have to be addressed in Washington. But despite Afghanistan, the Arab Spring, and protests in places like Ukraine, corruption is not something many decision-makers see as critical to our national interest.

WHAT DID YOU LEARN FROM THESE EXPERIENCES?

CHAYES A lot. One point is the importance of talking to ordinary people. When I was working in the Pentagon, something would happen and I would want to hear regular Afghans’ reactions. I’d call people, or, if I was there, I would ask them. And I would get an answer I didn’t expect. After eight years living there, I still couldn't predict the answers—though as soon as I heard them, I would slap my forehead: ‘Of course!’ It reinforced the critical importance of primary sources.

Photo credit:

Eve Chayes Lyman

Sarah Chayes is focused on determination, not hop

Connected to that, I learned how often decision-makers get captured by specialized bureaucracies—which sometimes get married to a point of view for reasons that have nothing to do with the mission. Leaders need to ensure they have a variety of independent sources of information right in their face. It can be very painful both for the leader and for the staff.

Another point has to do with the power of truth. I used to think that when the truth is known, changes automatically ensue. I thought that when I demonstrated that corruption was fueling the Taliban insurgency because of the outrage it was generating, U.S. policy would change. But it didn’t. That’s when I understood the force of the convenient myth. For example: ‘Afghans are culturally corrupt. We’re trying to do too much in Afghanistan. We’re trying to impose democracy on people who aren’t ready for it.’ I heard that all the time. That narrative makes us feel good.

Well, we didn’t do any of that. What we imposed on Afghans was a mafia—a criminal organization that masquerades as a government—when they wanted a democracy.

We just assume we’re the white knights. Trying to influence policy in such an environment is challenging because you almost have to dismantle people’s positive image of themselves. And they will resist. So, the notion that telling the truth in a convincing way will cause a whole bunch of dominoes automatically to fall is incorrect.

WHY AREN’T DETERMINATION AND HOPE ONE AND THE SAME?

CHAYES Hope is a conviction that the future of a country or an endeavor will be positive, almost no matter what you do. My point is that you have to apply yourself, regardless of what you think is going to happen. Hope is both irrelevant and, to some extent, maybe counterproductive because it may blind you to obstacles and make you miscalculate what must be done.

HOW CAN WE EACH EFFECT POSITIVE SOCIAL CHANGE?

CHAYES Ground yourself in truth. If you are in a senior leadership position, ensure—and you will have to break china to do this—that you are not surrounded by a bubble of people telling you what the system wants you to hear. Break the homogeneity of the people in your immediate circle. Bring in contrary voices and protect and empower them. It’s painful to do this for two reasons. First, it will create management headaches, and, second, it’s cognitively difficult because you want to believe the convenient myth. We all do.

If you’re not number one, find channels to get reality to the top. Don’t let telling your immediate superior suffice because there are layers of filters. If you think it’s important, make sure people in a decision-making capacity have the information. Make allies. Create an environment where other positive people can move in and then, suddenly, you start to get a critical mass that allows you to make a difference.

Finally, get out of your comfort zone. Walk around in unfamiliar neighborhoods that aren’t comfortable to you. Interact with people who are different from you and listen to them. Whatever your background, go to the other extreme. I’m not saying you have to go to Kandahar. People who come from a different perspective are all over the place. They’re right next to you.