How five members of the Walden Community are preparing teenagers for lives of leadership.

By Lindsay Downey

These dynamic transformations occurred thanks to Walden University alumni, students, and faculty who are changing teenagers’ lives through paths of service. Empowered by all they’ve learned in and out of the Walden classroom and inspired by its social change mission, five experts share their best practices here on cultivating relationships with Generation Y and guiding them toward lives of leadership.

Step 1. Build a Culture of Giving

On a sunny afternoon outside a nursing home in Cayce, South Carolina, shortly after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, a high school student named Ron Cole pushed a nursing home resident in a wheelchair. Cole had fled to Cayce in the aftermath of Katrina, and the nursing home resident happened to be a direct descendent of a signer of the Declaration of Independence. As the teen wheeled the aristocrat around the grounds, they shared stories of their divergent upbringings while Cole’s teacher watched in amazement. “This child, who completely has nothing, who’s a refugee from one of the poorest parts of the country, is having an enjoyable conversation with a man who comes from an extremely elite, historic family,” recalls Dr. Sarah Jane Byars ’08, Doctor of Education (EdD), who taught Cole at Brookland-Cayce High School.

This experience led Cole to take a special interest in visiting nursing homes, and he frequently stopped by Byars’ classroom to inquire about new volunteer opportunities. Byars, a 38-year classroom veteran, believes Cole embarked on that first nursing home visit because she didn’t push him too hard when she talked about volunteer opportunities with Character Club, a group she launched in 2001 to bring honors students and at-risk teens together to work on service projects.

Byars was drawn to Walden because it was one of few universities that offered an EdD in Teacher Leadership, designed for people who intend to stay in the classroom. The program has inspired her to work even harder to help teens see the benefits of positive social change. When they witness Byars pick up trash along the roadways or kneel at the bedside of a nursing home resident, it speaks volumes to her students and opens them up to a new world in which they can make an impact. “Service work gives teens a way of giving back rather than always being the charity case,” Byars says. “It raises their self-esteem tremendously and gives them a sense of contribution.”

- Never get angry about their unreliability. Teens need invitations to do service work—usually numerous ones. Just invite them again, alleviating any sense of pressure. Often, they consider joining you but need time to muster courage. —Dr. Sarah Jane Byars ’08, Doctor of Education (EdD)

- Model altruistic behavior. If you’re going to ask kids to do a service project, be there with them. Take time to engage students in conversations and lessons that focus on why we try to do things to help others. Our country has a great tradition of giving, and it pays to let students know they are carrying on that tradition. —Tom Webb, faculty, The Richard W. Riley College of Education and Leadership

- Make altruism the norm in the family by giving to charity and showing benevolence of shared time, energy, and money. —Dr. Helen Sung ’07, PhD in Education

- Suggest that students do things they’re passionate about. Leaders have to show some sort of passion in life. —Jason Lum, faculty, School of Public Policy and Administration

- Provide exposure to cultural activities and activities that highlight service. At-risk students may have no concept of what it means to go to a symphony or even to the next town. A world they hadn’t imagined opens up to them and they become inspired. —Susan McGilloway, student, MS in Mental Health Counseling

Step 2. Earn Teens’ Trust

A troubled young felon needed someone to talk to. But like many students from disadvantaged backgrounds, he had difficulty trusting people outside of his cultural group, says Susan McGilloway, an M.S. student in Mental Health Counseling. As a student support services specialist at the Community College of Baltimore County’s Center for Adult & Family Literacy, McGilloway talked with the young man, who was studying for his GED exam and searching for an employer willing to look past his criminal record, and slowly broke through his emotional wall. He eventually opened up about his family and even shared a sonogram with McGilloway as he spoke of his unborn child. “He said, ‘I don’t have anyone to talk to. Nobody listens to me,’” McGilloway says. “He seems so macho but he’s starving for someone to pay attention to him.”

When she began her work with at-risk GED and ESOL students, McGilloway quickly realized the immense challenges they faced in getting their lives on track. She knew she needed to enroll in a graduate program to further her work with at-risk teens, and when she read about Walden’s social change mission and the counseling component incorporated in its degree program, she knew she’d found the ideal fit. Through her degree program, McGilloway is learning the importance of collaborating with communities in her mission to empower at-risk students.

To gain the trust of disadvantaged teens—who often don’t have role models—adults should first show interest in them, McGilloway says. She strikes up conversations with young people about their families and about pop culture and social networking. It’s important to talk to at-risk students about things they care about to forge a relationship. “It takes a lot of patience and a lot of bonding to get to a point where they trust you’re not going to take advantage of them or marginalize them or oppress them,” McGilloway says.

How to Build Trust With Teens

- Be real. Teens can spot a fake a mile away. They need to know we really are who we say we are, that our caring is genuine, and that we make mistakes. —McGilloway

- Don’t target students—let them choose you. Many students are eager to spend time with an adult who is genuinely interested in them. Encourage them to bring friends to volunteer. —Byars

- It’s important that we can relate to teens on their level and talk intelligently about things like text messaging, Facebook, and Twitter. —McGilloway

- Find ways to chat about their personal lives and interests. Listen to their answers and reflect their responses with empathy. Keep conversations low-pressure. Offer suggestions but never lecture. —Byars

- Once you gain the trust, talk about your own experiences. Say, ‘This is what happened to me when I was an adolescent—maybe it’s going to help you.’ —Sung

Step 3. Teach Them About the Power of Education

Step 3. Teach Them About the Power of Education

When a Hmong-American immigrant he’d been working with lost both parents to a murder-suicide, Jason Lum, faculty member in the School of Public Policy and Administration, offered support to the teen and encouraged him to focus on his academics. “I constantly reminded him that education was the only escape valve from the violence dominating his neighborhood,” says Lum, adding that the young man is now thriving in college.

If anyone knows how education can elevate a disadvantaged person to a level playing field, it’s Lum. Growing up the son of a blue-collar worker and a homemaker, Lum knew that if he wanted to go to college, he’d have to pay for it himself. “There was no other option,” he says. “My parents had no money.” Lum’s family encouraged him to aspire to the best schooling possible and instilled a sense of resourcefulness in their son. “My parents always taught me that I’m not owed anything from anyone,” says Lum, who won more than 40 scholarships for a total of $250,000—enough to pay for his bachelor’s, master’s, and law degrees. “If you want something, you have to go and get it.”

Through his ScholarEdge College Consulting company, which he founded in 2000, Lum inspires students to reach for their educational goals—even if there’s no funding in sight—and coaches them on winning scholarship and grant money in part by pursuing their interests. “I’ll meet students who think that the way you want to impress a scholarship committee is by attending a summer institute somewhere when really what the student wants to do is spend a month volunteering to build homes in New Orleans,” Lum says. “I tell them to do things they’re passionate about.” In sharing the story of how he transformed himself from blue-collar background to civil rights attorney, professor, and entrepreneur, Lum is not only helping teens get to college—he’s proving persistence can pay off well after the scholarship money rolls in. “When you see a problem, you don’t just put your head in your hands,” he says. “You do something about it.”

- Help them think long-term. Reinforce the idea that in America, we don’t all have the benefits of coming from wealth, but that education is the great leveler. School and life may present some roadblocks, but the ultimate goal is to secure great knowledge and better yourself. —Lum

- At-risk students often don’t have people within their families who can help them navigate the education system. We need to prepare them academically and with the non-cognitive skills they need to survive in post-secondary education. —McGilloway

- Encourage them to have goals and talk about the steps to get there. Discuss how higher education is a way to reach their goals, open doors for opportunities, and network with people in the field. —Sung

- Build on strengths. The self-esteem of Generation Ys is very fragile. They are searching for their giftedness and beauty, and need all the encouragement they can get. —McGilloway

- Teach teens that you don’t spend money on education—you invest it. Pursuing higher education is a pathway to greater social good, which really has no price tag. —Lum

Step 4. Nurture Emotional Intelligence Through Reciprocal Relationships

This supported Sung’s research, published in School Psychology International in April 2010, which found emotionally intelligent teens had open, collaborative relationships with their parents. “Teenagers who had high emotional intelligence said they liked to talk to their parents about everything,” Sung says. Parents who were critical, directive, and didn’t listen to their children growing up found that as teens, their kids shut them out, turned to their friends with their problems, and rebelled against parental advice.

To raise emotionally intelligent, altruistic teens, parents have to create reciprocal relationships with their children during their formative years. “If you haven’t developed the trusting relationship, it’s much harder to start it when they’re adolescents,” says Sung, who works as a school psychologist for Cupertino Union School District in California, an adjunct professor at Alliant International University, and a private consultant for educational and emotional well-being.

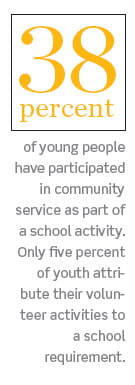

Adults should also engage young people in philanthropy to increase their emotional connectedness and to help them grow into philanthropic leaders, which will spark positive social change for decades to come. “When teens do service work, it helps them see beyond themselves,” Sung says. “It promotes caring, altruism, and perspective—the qualities that enhance who we are as human beings.”

How to Develop Collaborative Partnerships with Teens

- Don’t bend your character or values to have relationships with teens. Bring them up to your standards. They want someone to admire and someone to inspire them. —Byars

- Respect that Generation Ys live on a very different timeline than us. What seems urgent to us is not always seen as urgent to them. Their priorities are not always ours. —McGilloway

- Be optimistic. We live in the most interesting of times, with an interconnected world, unparalleled travel opportunities, and distance education. Remind teens there is no better time to be alive than today. —Lum

- Provide students with an opportunity to make decisions regarding things they will do to help others. When given a choice, they are much more engaged and enthused. —Webb

- You have to be a good listener and you cannot be judgmental. Allowing them to talk is sometimes really important. Recognize the goodness in teenagers and let them know how much they are valued. —Sung

LEARNING TO GIVE

Free Philanthropy Lesson Plans

During his 33 years as a seventh grade teacher at Fulton Public Schools in Middleton, Michigan, Tom Webb, faculty in The Richard W. Riley College of Education and Leadership, engaged his students through classroom lessons on civic responsibility. In 1997, he served as one of 35 Michigan teachers who helped launch Learning to Give. As the curriculum arm of the youth philanthropy organization The League, Learning to Give offers educators more than 1,400 free lesson plans to promote community service in their classrooms. Webb wrote Learning to Give lesson plans that weaved in service ideals, and afterward, students applied what they’d learned through community projects—whether it was picking up trash along the banks of a river or raising money for the local animal shelter. Teaching service-based lessons in the classroom helps students understand America’s history of civic engagement. Educators should present regular lessons rooted in philanthropy to instill in students a natural desire to help. “Do not wait for a big catastrophe to occur before doing something,” says Webb. “Conduct regular and local service activities at school. If a major event occurs—such as the earthquake in Haiti—students will automatically step up and ask to get involved.”

Get free service-based lesson plans.

Interested in playing a role in the lives of teenagers?

Register with the Walden Service Network, a free online resource where you can find service opportunities, record volunteer hours, and network with members of the Walden community who are ready to lend a hand to your cause. Registration is open to all. Visit www.WaldenU.edu/servicenetwork to get started.